The history of English gardens

Here’s a fascinating guest post by one of our volunteers, Emily, who’s here to enlighten us all about the history of our beloved gardens…

Gardens, we all take them for granted these days don’t we? Whether it’s a little plot at the back of your house, or a ginormous plot of land belonging to a large estate, the garden is a place where we can retreat and where nature can thrive. But have you ever thought about the origins of our gardens, and how they evolved over the centuries? Well, if you are sitting comfortably, then I’ll begin…

Tudor garden twists

Gardens in the past changed with what was fashionable at the time. If you didn’t have the latest garden trend, then you were nobody. In the early days of the Tudor period, gardens were, like today, places to socialise and to take exercise. In those days, when practising the wrong religion could get you into BIG trouble, rich landowners would hide religious symbols within their gardens, as well their houses. A maze was often a feature in these gardens, and guest could enjoy them often oblivious to the notion that they may be a religious symbol. Instead what they saw was perhaps a form of entertainment, especially when catch a dashing suitors’ attention was part of the fun!

By the time of the Stuarts, some considered the style and symbols of the old Tudor gardens, ahem, out of date, and had them redesigned to meet the fashionable standards of the time. Trees and paths were the order of the day! Oh there were flowers too, but planted in straight lines. The English were very keen to stay ahead of their rivals, the French, and it was very much a case of “anything you can do, we can do better ”. So English gardens became very French in style, in an attempt to out do them. An example of this is the famous garden at Hampton Court. A garden for royalty and the well to do, designed for walks and parties. A bit like today really!

The illusion of untamed nature

Fast forward to the Age of Enlightenment and the gardens of the stately home changed dramatically. Out went the formality and in came the ‘nature-controlled’ gardens, ones created by man, but with the illusion that they were perfectly natural. We see this most in the gardens of the stately homes we know and visit today, from Stowe in Buckinghamshire to Castle Howard in Yorkshire. Like the Tudor gardens, these could also have hidden meanings. From the political views of the owner, to telling stories according to folklore and fairy tale, the garden became a place for the well-to-do to play out their fantasies.

These gardens didn’t come cheap though, if you were hoping to build a grotto for your back garden for a small sum, you’d need to think again! One man responsible for making these gardens a reality was Lancelot “Capability” Brown – THE man for job. The prices attached to his gardens were eye-wateringly expensive, particularly as everything was done by hand, no JCBs here! Planning a visit to your local garden centre to buy things off the shelf wasn’t an option, and much of it, like the statues, had to be sculpted from scratch.

BUT if you DID have the cash, then you could have everything you could possibly want. Waterfalls, temples, grottos, you name it. The temples and ruins that were constructed for these gardens were often Grand Tour inspired. These trips or ‘tours’ were taken by the aristocracy to places like Greece and Italy, and from them, they bought back classical ideas for their gardens. It was the time of ‘the Romantics’, romanticising the ancient histories of Rome & Greece. It’s something we still do today, we all like a bit history in our gardens…

Kitchen gardens

In the Georgian and Victorian periods, the garden changed again, with clashing colours mixing in the borders, and the introduction of greenhouses for growing plants and produce normally grown in a warmer climates, like ferns and palm trees! Growing fruit and veg in the garden had of course been around for some time, with many stately homes having their own kitchen gardens built for the purpose. Back in the Georgian period, the way to show off your wealth was to have a ‘pinery’ for growing, wait for it, pineapples! Why were they a symbol of wealth you ask? Because pineapples are notoriously temperamental and an absolute pain to grow!

The humble back garden

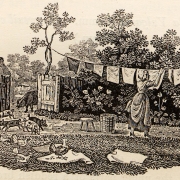

By the Victorian era, the garden started to become more accessible to the masses, and those who were lucky enough to have their own back garden for their property, used them primarily to grow produce for their families. Gardens became more functional places over spaces to socialise. During WW1 and WW2 the kitchen garden was considered more important than ever before, growing whatever was needed to survive.

Today, many gardens combine the role of food provider and leisure space, taking snippets of inspiration from gardens throughout history and all over the world. Whether they are well loved and cared for or messy, neglected and in need of a little love, they’re something that we all recognise and take pleasure from. The fashions and designs of gardens will change, but the need and desire for them will always remain the same.